I grew up in a HOT climate (below), where we didn’t have to deal with the kind of weather that we have right now in most of the country. Back home, occasional road signs near overpasses nonchalantly suggest that “Ice Forms on Bridge First” – as if something more cautionary like “Watch for Ice” would be too sensational and presumptuous.

It wasn’t until graduate school that I first witnessed the phenomenon of salting roads and sidewalks. I was surprised to discover that the salt sprinkled around campus was often colored – blue or green or yellow. Apparently, this “salt” isn’t simply salt.

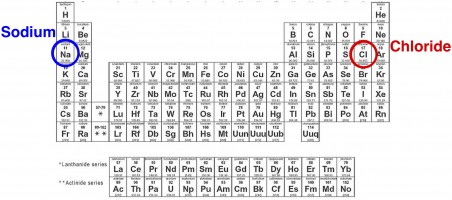

When people say salt, they usually mean sodium chloride (NaCl) – the stuff that you keep on the table next to the pepper shaker. But in chemistry terms, NaCl is just one type of salt. And in fact, road salt actually contains several different types of salt – not just NaCl.

When people say salt, they usually mean sodium chloride (NaCl) – the stuff that you keep on the table next to the pepper shaker. But in chemistry terms, NaCl is just one type of salt. And in fact, road salt actually contains several different types of salt – not just NaCl.

What is a Salt? To a rough approximationexceptions include salts of transition metals, such as silver salts, a chemical that qualifies as a salt involves a bond between an atom from the left side of the periodic table with an atom from the right side of the periodic table. Such a bond is termed an “ionic” bond.

Salts in Road Salt. In addition to NaCl, road salt formulations usually contain other chloride salts such as magnesium, calcium, and potassium chloride. Sodium acetate and calcium magnesium acetate may also be added to the mix, as well as some basic salts such as calcium hydroxide to help counter corrosiveness.

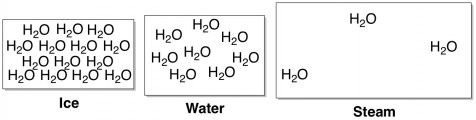

How Do Salts Melt Ice? The difference between frozen water (ice) and liquid water is how close the individual water molecules stick together. When water is very cold, the molecules don’t have enough energy to bounce around much, and so they just stay huddled up next to each other in a solid ice crystal. When energy is added in the form of heat, the molecules become bouncier and space out quite a bit, with the freedom to fluidly move around each other as they please.

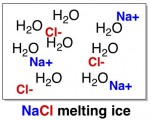

Like most salts, the salts in a road de-icer are highly soluble in water. When these salts come in contact with ice, they try to dissolve. The ions (charged atoms) from the salt squeeze in between the water molecules and push them apart, melting the ice into a liquid. More technically, this phenomenon is called freezing point depression.

OK, So Where Does the Color Come From? Google knows a lot of things, but it doesn’t seem to know exactly what gives sidewalk salts the blue or yellow colors that I typically see. The best I can find is that a “color indicator” is commonly added to brands of blue-colored salt like Streamline’s Blue Heat Ice Melt.

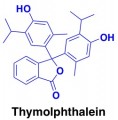

However, a 2004 patentEnvironmentally safe and low corrosive de-icers and a method of manufacturing same suggests that phenolphthalein can be used as a reddish dye for road de-icers. Phenolphthalein is an organic molecule that serves as an acid-base indicator. At a basic pH, it’s colored reddish, but at a more neutral or acidic pH it has no color. Because road salts are usually somewhat basic (to counter corrosiveness), phenolphthalein would be colored red in the road salt formulation, but would “disappear” as the dissolving salt gets diluted or mixed with acids in the environment.

The blue or green salts that I usually see on the sidewalk could contain a similar acid-base indicator, like thymolphthalein.

In conclusion, sidewalk salt is actually pretty complicated. I think I prefer the simplicity and comfort of a warmer climate.

Like most salts, the salts in a road de-icer are highly soluble in water. When these salts come in contact with ice, they try to dissolve. The ions (charged atoms) from the salt squeeze in between the water molecules and push them apart, melting the ice into a liquid. More technically, this phenomenon is called freezing point depression.