This is part 2 of a 3 ± 1 part series on navigating the language of chemicals. Read an introduction and part 1 if you wish.

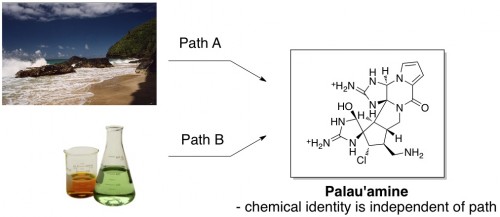

Efforts to make sense of the health and safety information for any given product can be complicated by pervasive buzzwords, hyperboles, and myths relating to chemicals. In order for the reader/viewer to stay calm and think scientifically, it’s important to be aware of the presence of these attitude-modifiers.

Buzzwords

If popular writing is tossing around numbers, it’s only fair for it to stick to the rules of mathematics. If Ikea lists a $1000 couch as on-sale for $600, they’re going to describe it as 40% off. Not 75%, not 12% – the language of basic arithmetic isn’t arbitrary. When the word “percent” is used in popular writing, its meaning is identical to its meaning in a mathematics journal.

But for some reason, the language of chemistry is used rather whimsically in popular writing. A newspaper article about preservatives in beef jerky rarely restricts itself to using chemistry terms in a chemically correct way, despite the fact that the article is playing on chemistry territory. The most obvious example is the word “organic”, which has been so corrupted that you can now purchase organic sea salt.

Many of these words carry a positive or negative connotation in popular writing, and can be used to evoke a certain attitude in the reader without necessarily saying anything meaningful. Thus the savvy reader who wants to think rationally and scientifically about the chemicals in their beef jerky should be aware of these chameleon words. Such words may be conveying attitudes and emotions more effectively than they convey actual facts.

Hyperboles

The biggest (chemistry-related) exaggeration plaguing popular communication is probably the insinuation that all chemicals are bad. In my last post, I tried to look at why this hyberbole is just plain silly, and even the least scientifically inclined consumer would likely agree if they sat down and thought about it.

But there’s another more subtle notion which, though also hyperbole, seems to be quite widely accepted as fact:

“Some chemicals are always bad.”

This blanket statement, though much less ridiculous than “all chemicals are bad”, can still undermine one’s efforts to think rationally, for the following reasons:

(1) It can’t ever be proven.

(2) It can indeed be disproven for individual chemicals.

(3) This notion dismisses the important concepts of quantity, concentration, and context.

(3) This notion dismisses the important concepts of quantity, concentration, and context.

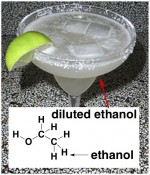

To illustrate #3 – the importance of quantity, concentration, and context, consider the chemical ethanol (alcohol). When consuming ethanol, it’s critical to consider quantity (one drink vs/ 6 or 7), concentration (tequila shots vs. margarita), and context (drinking on the couch vs. in between roller coaster rides at Six Flags).

And to illustrate #2, consider the case of sulfur mustard (mustard gas). Sulfur mustard is a chemical that is very nearly always bad, perhaps closer to being “always bad” than any other chemical. Its historical use as a weapon speaks for itself. Nevertheless, sulfur mustard was one of the very earliest experimental chemotherapies for treating otherwise uncurable cancers. Its success as such was extremely limited, and the negative side effects of sulfur mustard exposure are too awful to warrant its clinical use today. But, in a way, sulfur mustard helped to kick off research that eventually led to more acceptable treatments for cancer.

And to illustrate #2, consider the case of sulfur mustard (mustard gas). Sulfur mustard is a chemical that is very nearly always bad, perhaps closer to being “always bad” than any other chemical. Its historical use as a weapon speaks for itself. Nevertheless, sulfur mustard was one of the very earliest experimental chemotherapies for treating otherwise uncurable cancers. Its success as such was extremely limited, and the negative side effects of sulfur mustard exposure are too awful to warrant its clinical use today. But, in a way, sulfur mustard helped to kick off research that eventually led to more acceptable treatments for cancer.

Myth #1 – “Natural = good and synthetic = bad”

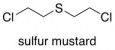

There’s an entire genre of organic chemistry that publishes papers entitled “Total Synthesis of the Natural Product Blah-Blah.” In such papers, the authors describe the successful construction of a complicated molecule found in nature (usually in a sea sponge or something) in the laboratory starting from small, inexpensive chemicals. The synthetic molecule produced in the laboratory is exactly identicalexcept for 13C abundance, but that's irrelevant to the molecule found in nature. Thus if the natural product Blah-Blah is “good”, then so is the man-made chemical Blah-Blah. The properties of a chemical are independent of the path taken to construct it, whether in a lab or in a sea sponge. (Natural product below = palau’amine.)

As theyI don't know who 'they' is say, though, every myth has a germ of truth. The basis of this particular myth is the (probably true) notion that it’s not healthy to consume a ton of chemicals taken out of the context in which they are naturally found. As one astute commenter pointed out last time, “the whole ‘natural’soybean is not frequently associated with health risks, but soy protein isolate has been cited many times.” (I don’t personally know much about this, but it illustrates the bit of truth in the natural/synthetic myth.)

Thus, if sea sponges were good to eat, that wouldn’t necessarily mean that a natural product isolated from a sea sponge (or synthesized in the laboratory) is good to consume in large quantities.

Myth #2 – “If you can’t pronounce it it’s bad.”

Even the most innocent-looking chemical has a beastly sounding official chemical name, thanks to the nomenclature rules developed by IUPACInternational Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Table sugar, for example, can also be correctly called:

(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[(2S,3S,4S,5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]oxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-3,4,5-triol

Some chemicals, like sugar, are lucky enough to have easily pronounceable common names that serve as an acceptable substitute for their more scientific name. Unfortunately, some chemicals are best-known by names that the other chemicals make fun of on the playground.

Other Stuff. I’m sure there are lots more instances of buzzwords/hyperboles/myths regarding chemicals in popular media. If anyone has any more to contribute, I’m curious to hear!

I think another chemist interpretation of “natural” would be “impure.” From a pharmaceutical chemistry perspective perhaps also “unregulated.”

Also, I have a really hard time pronouncing the word “cloths.” (Try it a few times) Does this mean cloths are bad?

I’m really into healthy eating, but as a former chemist (now studying genetics) this sort of stuff absolutely enrages me. Most of my friends can probably relate stories of me babbling about how just because its made in nature (“natural”) doesn’t mean it isn’t harmful, and just because a compound is recreated in lab doesn’t mean it isn’t as good as the original compound found in nature. THANKS!

Language, unlike elements, are not immutable. Words move between languages, cultures, and their meanings morph. Over time, a word can take on meanings radically different from the original inception. Therein lies the beauty of language, poetry, & communication. But we, as scientists, want structure in our taxonomy. For consistency’s sake, we need IUPAC names, protein databases, & binomial nomenclature.

As a consumer and scientist, I laugh when I see “organic salt” or “organic dry cleaning,” knowing that these nonsensical constructions are ridiculous from any angle. Chemists have a strict definition of “organic.” So does the USDA. Both definitions are valid; in the case of the USDA definition, there is a legal implication, to which a farmer or manufacturer must comply. In chemistry, it’s much simpler: carbon = organic. I have no idea how salt can be organic in either definition, which is why I laugh. Dry cleaning may use carbon-based solvents, but I’ve never seen the USDA organic stamp in a dry cleaner’s window…

It is the domain of poetry to challenge definitions through experiment and wordplay. Buzzwords – any word – however, should be used accurately in chemistry, and when dealing with consumer products. What I take away from your post is something that has been gnawing at me for a while – namely, the general illiteracy with regards to science and critical thinking. Too many people think of science as too complicated, and make no effort to educate themselves about how science works, or how to critically think for themselves. They feel empowered by reading a label, but don’t stop to actually find out whether that “unpronounceable” word in the list is natural or synthetic, healthy or unhealthy, good or bad. I think your points are on target, but it’s not the words, or language that’s the problem, it’s the fact that people don’t want to think for themselves.

Loved the post! Thanks for informing the masses! Ah, buzzwords!

Thanks for the comments all : )

@Unstable Isotope – Agreed that “natural” can mean unpurified (maybe not for organic chemistry, but other sorts of science). Also, I avoid awkwardness by saying the word “fabric(s?)” instead of cloths.

@Bliss – good point. There are plenty of examples too of things-found-in-nature that will kill you!

@Phytoalchemist – A fair point. But I guess I’m an optimist, because I find it difficult to accept that the majority of people simply don’t want to think for themselves. I agree that that science can appear so intimidating that many people don’t realize they have the mental tools to handle scientific reasoning. On another note, I really like your assessment of language.

I would quibble with you over the chemist’s definition of “chemical”. What you have described is more correctly a molecule, which certainly is a chemical, but you can have two or more (identical) molecules and still refer to the collection as a chemical.

Nitpicky I know. Other than that, I loved the post, especially the graphic that I was complaining about. It nicely condenses a lot of thoughts that I’ve had.

I agree with you, and I am also thinking of “chemical” as a collection of identical molecules. Can you suggest a simple but more precise way to phrase the definition of a chemical?

To use it in a sentence: baking powder can be broke down into two chemicals (maybe 3), but no further – sodium bicarbonate and potassium bitartrate.

I suppose “chemical” can be used almost synonymously w/ “molecule” in some contexts, but it means more the bulk stuff. It also depends on what you or I mean by “divided into” – whether we mean mentally dividing something up (categorizing) or physically.

Thanks for the quibble!

Unfortunately terms like “organic” and “nectar” have specific legal meanings (far from commonsensical) in some contexts that have made them little more than marketing tools. I have seen “organic apples” that had been treated with copper sulfate and “100% strawberry nectar” that contained a ridiculous amount of high fructose corn syrup. Industry and/or regulatory groups have defined the terms to allow such usage.

Bliss:

Here’s one you may know.

About 15 years ago, a certain breakfast cereal ran a series of ads stating, “It’s a fat-free natural energy source. Try it for a week.”

Obviously, they weren’t expecting people to compare it with other fat-free natural energy sources, like coal and uranium.

Some people often also create that natural is inoffensive.

for exemple when you use Essential Oils of product to cure yourself people often say that they can put all the quantity they want because that’s natural product and so that doesn’t hurt…

I think they should have surprises sometimes…

oh, they do!

Another fantastic post. There is a drycleaner near here that has a large neon “Organic” sign in the front window. I don’t think they mean what they WANT everyone to think they mean.

Also, if you’re not already planning this, how about some thoughts about “carbon-neutral” and “carbon-free” manufacturing of various items. I have a picture on my computer (somewhere) of “carbon-free” food of some sort. Hmm, I would love my bag full of oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and a bit of other things, but NO CARBON!?! Tasty…

Thanks for the comment, and for bringing up the carbon thing (yes we need carbon!) Carbon-free food sounds disgusting. It sounds like eating pure salt (can’t think of any other carbon-free food).

I actually do hear “carbon-neutral” thrown around in chemistry quite a bit. I suppose the term does sound a little silly, but we take it to mean a process in which no carbon atoms are “wasted”. It’s used in the context of fuels. Gasoline isn’t carbon-neutral – it gets burned into CO2 and stuff that just gets wasted as exhaust.

This set of chemical equations could be considered formally carbon-neutral, because the carbon-containing product (CO2) is the same as the carbon-containing starting material (CO2):

CO2 + 3 H2 –> CH3OH + H2O

CH3OH + O2 –> CO2 + 2 H2O

Another great post! Unfortunately, I don’t think the language of science will ever win out over the language of popular culture. The numbers are against us. I think we have to clarify what the terms actually mean within the framework of the language of popular culture. Don’t ask me how to do that. :/

When I do an aerobic workout for an hour and burn 1,000 calories or more, I become bathed in a mix of 100% natural and organic chemicals. Nonetheless this seems to have no positive connotation to my wife, though she gravitates toward anything organic in the grocery store. It also does nothing to make me more attractive to her and she insists that before I spend any time near her, I first use water and unnatural chemicals in the form of soap, to remove the covering of 100% natural, organic, formaldehyde-free stuff.

interesting blog about identifying chemicals. Hundreds of years from now, maybe, we will be remembered mostly as road-builders and glutamate-eaters.

My favorite saying is “If you can’t pronounce it it’s bad.” So what this means is that if you have good vocabulary skills nothing is toxic. The worse your vocabulary skills are the more dangerous the world you live in is!

Great series of blogs, thanks.

Fun post! I like it.

I wanted to make a quick clarification. The organic sea salt you have linked to is “organic” not because of the corruption of the term, but because some countries have organic certification standards for salt, ie, no unapproved solvents, source testing for contaminants, etc. While other countries may have this certification, USDA organic standards do not certify salt, so you will rarely see this in the US.

Thanks for making this point! Yes, there is definitely a difference between the chemistry version of “organic” and the USDA version.

One of the oldest myths in science is that Nature is random (Heisenberg relations) but Einstein did not believe it saying famously “God does not play dice”

Recently a challenge was given to show Einstein correct or to “Shut the hell up”

I have taken the challenge and posted the first four parts of my reply. The answer to this question (one of the top ten on Wikipedia physics) will take a couple more blogs. There are serious critics to this but my answer is pedagogical and anyone should be able to follow.

I invite you all to follow along–I am a chemist, not physicist, and so my language is more chemical than physics.